1. Childhood

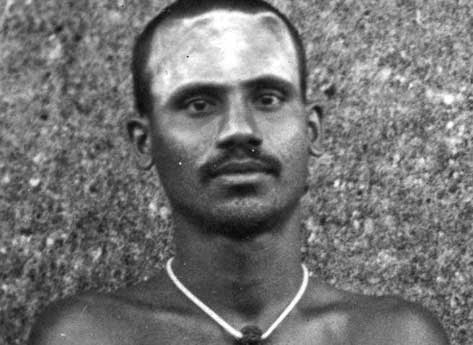

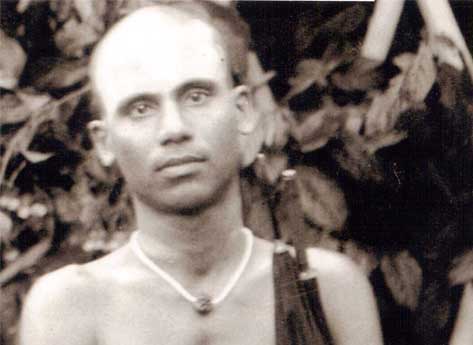

THE STORY OF SRI ANNAMALAI SWAMI

Sri Annamalai Swami talks about his childhood

This is the story of Sri Annamalai Swami, narrated by Swami himself. A story of how a child with almost no education but showed very early signs of spiritual maturity, came to meet his Guru Bhagavan Ramana Maharashi and by His grace, attained Self-Realisation.

Sri Annamalai Swami used to recollect and share these incidents with devotees who came for his Satsang at the Ashram. As he narrated them in Tamil, his disciple Sundaram Swami would translate it into English for devotees who did not know Tamil. Some of these translations were edited by David Godman and published in the book ‘Living By The Words Of Bhagavan’.

Birth

I was born in 1906 in Tondankurichi, a small village of about 200 houses. My father was an important person in the village. In addition to being a farmer, an astrologer. a painter and a builder, he also knew how to construct statues and make gopurams (temple towers). Soon after I was born my father and another astrologer met to discuss my horoscope. Both of them came to the conclusion that I was likely to become a sannyasin (Hindu monk who has renounced all ties with his family and the world). My father, who was not pleased by this prediction, decided to avert the possibility by denying me a proper education. He had the notion that if I did not learn to read and write, I would not be able to read the scriptures and never develop an interest in God. As a result, when I had just about mastered the alphabet I was taken out of the local village school and set to work assisting my father in his fields.

My father, suspecting that I might try to go back to school without his knowledge or consent, tried to ensure that I remained virtually illiterate by telling my mother, ‘If he goes to school again, don’t give him any food’.

A short time after I was taken out of school, when I was passing through a nearby village called Vepur, I heard a visiting scholar give a lecture. He told the villagers, ‘It is good to become educated. Even if you have to support yourself by begging while you are studying, you should study as much as you can. Only through education can we know about the mysteries of life.’ On returning home I went to my father and complained, ‘l listened to a scholar in Vepur today, who talked about the value of education. You are not permitting me to go to school.’

My father dismissed my challenge by saying ‘Oh, we are just farmers. We only need to be able to write well enough to sign our names.’

I had to self-study

I was not satisfied with my father’s attitude or answer and decided to try and study by myself. decided to try to study by myself. I got hold of two books, one containing the stories of King Vikramaditya and the other the verses of Pattinatar (a 9th century Tamil poet and saint), and tried to teach myself to read.

The one who renounces the home is crores of times greater than the one who, living as a householder, does many punyas and dharmas (meritorious acts). The one who renounces the mind is crores of times greater than the one who renounces the home. The one who has transcended the mind and all duality, how can I express the greatness of that person?

Although I had never come across statements like this before, I had always had a natural inclination towards the spiritual life. Nobody had ever talked to me about religious matters, but somehow I had always known that there was a higher power called God, and that the purpose of life was to attain this God.

Intuition about God from young

Without being told, I instinctively felt that everything I saw was somehow illusory and not real. These thoughts, along with the idea that I should not become attached to anything in this world, were part of my consciousness even in my earliest boyhood.

I remember one incident which happened when I was only six years old. I was walking with my mother near the village when a sādhu in orange robes walked by. I asked my mother, ‘When will I become a sannyāsin like him?’

Without waiting for an answer, I started walking along the road behind the sādhu.

As I was walking I heard my mother expressing her disgust to the local village women: ‘Look what a useless boy he is! Even at this young age he is trying to be a sādhu.‘

My father, unfortunately, did not share my spiritual predilections. He did do an elaborate pūjā (ceremonial worship of a Hindu deity) every day for about half an hour, but his motives were entirely materialistic.

Once, while I was still a young boy, I asked him, “Why are you doing this pūjā every day?’

He replied, ‘I want to get wealth, I want to get land, I want to get gold and a lot of money’.

I told him, ‘These things are all perishable. Why are you praying for these perishable things?’

My father was astonished that I had an understanding of such matters at such an early age. “How do you know that these things are perishable?’ he demanded.

‘I know, that is why I am telling you,’ I replied. The knowledge was inside me but I couldn’t explain it or account for it in any rational way.

When my father discovered that I was taking an interest in spiritual matters, he tried to discourage me. He put many obstacles in my path and it was not until many years later that he finally conceded that I was destined to become a sādhu.

Good luck Mascot

While I was still quite young the villagers adopted me as a kind of good-luck mascot. Whenever anyone began to build a new house, I would be asked to put in the first frame. I was asked to pull out the first weed when the weeding started in the fields and during marriages I would be asked to touch the statue of Ganapati at the beginning of the ceremony. The most pleasant chore, though, was eating sweets. Whenever people in the village prepared sweets for a special occasion, I would be invited to come and share them. I don’t know when the villagers first came to believe that I would bring them good luck, or how they arrived at this conclusion, but the tradition persisted till I was about thirteen years of age.

My Spiritual practices began early

I became more acquainted with religious rituals on a visit to Vriddhachalam, a Saivite pilgrimage centre near my village. I observed some brahmins doing anushtānas ( a wide variety of religious practices) there and asked them to initiate me into these practices. They refused on the grounds that sudras (members of the lowest caste) were not permitted to practise these rites. Soon afterwards I saw some non-brahmin Saivites (followers of Siva) performing the same rituals. I learned these anushtānas from this group and performed them regularly when I returned to my village. My father had, despite his rather cynical attitude to religion, previously initiated me into Sürya Namaskāram, (a well-known ritual in which one repeats a number of mantras and then prostrates to the rising sun.) I added these new rituals to this one which my father had already taught me.

I adopted one other practice: each month, on ēkādasi day (the eleventh day of the lunar fortnight), I tried to meditate all night without falling asleep. I soon discovered that if I tried to meditate in a sitting position I fell asleep. I tried walking meditation, but even that didn’t work because I fell asleep while I was walking. After a little experimentation I discovered that I could fight off sleep by taking baths in the local river and by rubbing sand in thighs to induce pain. I also used to chew a piece of tobacco because I was told that chewing tobacco stimulates the rajoguna (one of the 3 gunas or qualities of creation that is responsible for action).

All of the above memories were narrated by Sri Annamalai Swami himself, during his Satsangs with devotees who came to visit him at the Ashram.

Related Content

2. Youth

In my youth I was very keen on maintaining an outward show of piety to demonstrate my commitment to the religious life. I wore a white dhoti, covered my head in imitation of Ramalinga Swami and put a lot of…

3. Coming to Bhagavan

Sri Annamalai Swami recollects the circumstances that led him to Bhagavan in the year 1928, when he was 22 years old. A prophetic dream came true for him. One can't help but wonder at the supreme power of the…

4. The Young Disciple

About ten days after my arrival I asked Bhagavan, 'How to avoid misery? This was the first spiritual question I ever asked him. Bhagavan replied, 'Know and always hold on to the Self. Disregard the body and…