2. Youth

THE STORY OF SRI ANNAMALAI SWAMI

A youth with a strong urge for spiritual advancement

In my youth I was very keen on maintaining an outward show of piety to demonstrate my commitment to the religious life. I wore a white dhoti (a cloth which is worn like a skirt), covered my head in imitation of Ramalinga Swami (a 19th century Tamil saint), and put a lot of vibhūti [sacred ash] on my forehead and body. I was quite attached to Ramalinga Swami at the time: I had seen a photo of him in the village which impressed me enough to visit Vadalur, the place of his samādhi . While I was in my early teens I acquired a copy of the tenth part of a work called Jiva Brahma Aikya Vēdānta Rahasya. I learned prānāyāma techniques (yogic breathing exercises) from this book and began to practise them in the temple in the forest.

Reading this book brought about in me a desire to make a more thorough study of the scriptures. Ordinarily, this would have been very difficult for a boy in my position, but an unusual combination of circumstances soon permitted me to fulfill my desire.

I found a place to practice my spiritual interests

The karnam (government accountant) in our village owned many religious books which he had inherited from his father. Being a busy man, he had no time to read them. His wife, a very devoted woman permitted me to come to the house and read the books. Every day she would prepare food, offer it to the Ganapati statue in her house, and then give the food to me. She herself would only eat after I had consumed this offering. I eventually moved into the karnam’s house and lived on this food offering that the karnam’s wife was preparing. Since my parents disapproved of my religious zeal, I completely stopped going to my family home. During this estrangement, which lasted three years, I never once visited them.

When my father got wind of this he was surprised because he had assumed that I was still virtually illiterate.

Deciding to investigate the matter himself, he came and secretly listened to one of our evening sessions. Afterwards he apparently remarked, ‘I cannot make him obey me any more. So, I will just give him to God.’

The karnam’s wife attended most of our meetings. She developed a strong interest in the works we were reciting, became a vegetarian, and lost all interest in worldly matters. Unfortunately she even lost interest in her husband. One evening he took me aside and said rather angrily, ‘Because of your association with my wife she has become like a Swami. She has no desires at all any more. I don’t want to keep you in my house any more. You must find somewhere else to stay.”

The other devotees overheard what the karnam had said. One of them told me. ‘We don’t need to do our reading here. We can easily find somewhere else to go.’

At first we thought that we should build a simple thatched hut for our meetings but by the end of the evening we had decided to build a proper math (ashram). Each of us pledged funds to the enterprise and within a short time the Sivaram Bhajan Math came into existence. I moved into the math as soon as it was finished and continued my sādhanā (spiritual practice) there by conducting bhajans (devotional songs] and by reading aloud the teachings of various saints.

When the math was finished I built a tannīr pandal (a place which serves free food and drinks to travelers and poor people on the main road that went through our village). With the help of some devotees I collected enough funds to serve kanji (rice gruel) every day to sādhus and travellers who passed through the village.

My parents tried to force my marriage

Soon after I had established myself in the math my parents decided to make one last attempt to wean me away from the spiritual life. As I was about seventeen years of age at the time they thought, “If we don’t take action soon he will almost certainly become a sannyāsin. If we can find some girl to marry him, he may become a normal householder and give up all these spiritual activities. Perhaps he will then become like all the rest of us.’

Without even bothering to consult me about the matter, they found a girl, made all the arrangements with her family, and then went out and bought all the provisions that are necessary to celebrate a wedding. I heard about all these activities through one of the women devotees who used to come to the Bhajan Math.

Many of these people (my parents were not among them) had a meeting and decided to cure my madness by violent means.

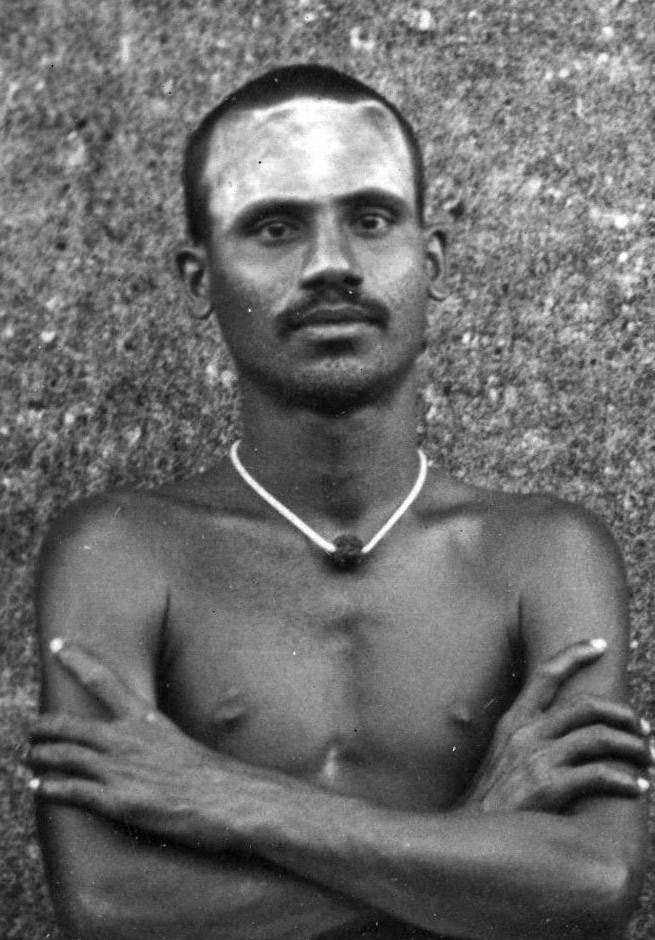

They collected me from the Bhajan Math, took me to a nearby lake, made a large cut in the top of my head and started rubbing lemon juice in it. This, apparently, was a cure for madness. Then they decided to pour buckets of cold water over my head. I think that they must have poured about fifty buckets over me.

While they were bathing me in this way I kept quiet and practised prānāyāma to keep my mind off the cold. I knew that it was useless to resist. When the villagers saw that I wasn’t reacting in any way to the treatment they became even more convinced that I was mad. Finally, when the treatment was over, they took me to one of the houses in the village. There, they made a sambar (spicy dish eaten with rice) out of bitter-gourd and made me eat it because they were under the impression that bitter gourd was another cure for insanity. About 100 people had gathered to watch all this.

While I was eating one, of them said to me, You are a good boy, born in a good family, but you have gone mad’. By this time my patience was finally exhausted. I have not gone mad,’ I replied in a rather irritable way. ‘Please leave me alone. Tell these people to stop crowding around me or give me a separate room where I can be alone.’ I was not expecting any kind of response, except possibly a further course of treatment, but much to my surprise they granted my request and permitted me to retire to one of the rooms in the house. Before they had a chance to change their minds I bolted the door and lay down on the floor to rest and recover from my ordeal.

A little later I got up and tried to meditate. While I was sitting there I overheard the head man of the village discussing my case on the other side of the door. ‘If you will permit me, I will get a promise from that boy that he will get married and lead a normal life. Because of these treatments his madness may now have gone.’ He knocked on the door and I let him in. Standing in front of me he said, very firmly, ‘Please give me a promise, because you are not mad any more, that you will get married like all the rest of us and lead a normal householder’s life’.

I replied, ‘I will promise you instead that I will become a sannyāsin. I clapped my hands while I was making the promise to show him how serious I was and that I had sealed the promise. The man left immediately. I then heard him exclaiming outside, ‘Ayo! Ayo! I asked him to promise one thing and he promised the opposite!’

My family paid no attention to my promise. I heard from a woman who visited me that my father was still secretly making plans to go ahead with the wedding.

I therefore decided that it was time to make a few secret plans of my own. First, I wrote a note to the girl who was supposed to be marrying me. My intention is to become a sannyāsin. I don’t intend to get myself entangled in a householder’s life. So don’t think that you are going to marry me. This will only cause you trouble.’ I arranged for someone to deliver the note to her house. Then, on the same day, I escaped from the house and made my way to Chidambaram (a famous South Indian religious centre).

I intended to take sannyāsa there, but I didn’t do it in any formal way. Not wanting to go to anyone for initiation, I did everything myself. I took a bath in the river, had my head shaved, put a necklace made out of rudraksha seeds around my neck, and dressed myself in a short dhôti and towel. I went back to my village in this new garb and announced to everyone that I was now a sannyāsin. My new appearance finally convinced my family that I was serious and that I had no intention of marrying. Very reluctantly they abandoned all their marriage plans because they knew that people who become sannyāsins remain celibate for the rest of their lives.

My parents finally gave their approval

I resumed my old routine and started to make plans for the kumbhābhishēkam (consecration ceremony] of the math. I invited several groups of bhajan singers from the surrounding villages and I even persuaded my parents to donate all the provisions that they had bought for my wedding. The food they donated enabled me to feed about 400 people. The other devotees who had contributed to the construction of the Bhajan Math supplied buttermilk, ragi (a kind of millet) and rice gruel to all the people who came. On the day of the kumbhābhishēkam the invited bhajan singers paraded through our village, performing in every street.

him Annamalai Swami)

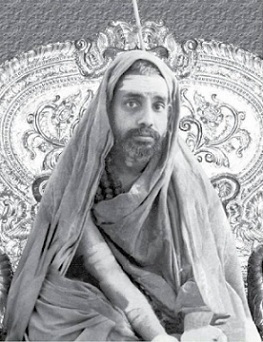

Meeting the Sankaracharya (Mahaperiyavā)

A few weeks later I heard that the Sankaracharya of Kanchipuram was planning to pass through the village on one of his tours. He was affectionately called Mahaperiyavā. When I heard this news I decided that I would try to make the Sankaracharya stop briefly in the village so that I could have his darshan (see his holiness). Knowing that there would be many people and animals in his procession, I thought that the best plan would be to supply them all with food and water. If I did this they would all have to halt for a short time while they ate my offerings. On the appointed day I prepared a large amount of buttermilk and kanji for the brahmins who would be accompanying him. I also stocked up on green leaves so that I could feed the horses and the elephants.

As the procession approached the village I raced up and down the line handing out green leaves. The Sankaracharya was being carried in a palanquin, but I couldn’t see him because the curtains were drawn. When I offered kanji to the people who were carrying him, they decided to stop and eat my offering. This caused the Sankaracharya to open the curtains to see what the delay was. I immediately prostrated to him. He looked at me in silence for a few seconds and then said, ‘After one mile I shall rest for a while. You can come and see me in that place.”

There was a small town called Vepur about a mile from the village. I discovered from one of his entourage that a bhikshā (food offering) had been arranged there and that the Sankaracharya would be staying in the Vepur Traveller’s Bungalow. There was a sub-inspector of police in our village who was quite a good devotee. When we heard that the Sankaracharya was staying nearby we both walked to Vepur to see him. A large crowd was milling around him when we arrived but I still managed to get near enough to touch his feet. His brahmin attendants complained, saying, ‘Non-brahmins should not touch him, but the Sankaracharya silenced them by saying, ‘He is a brahmachāri and a sādhu so it doesn’t matter’.

All of the above memories were narrated by Sri Annamalai Swami himself, during his Satsangs with devotees who came to visit him at the Ashram.

Related Content

3. Coming to Bhagavan

Sri Annamalai Swami recollects the circumstances that led him to Bhagavan in the year 1928, when he was 22 years old. A prophetic dream came true for him. One can't help but wonder at the supreme power of the…

4. The Young Disciple

About ten days after my arrival I asked Bhagavan, 'How to avoid misery? This was the first spiritual question I ever asked him. Bhagavan replied, 'Know and always hold on to the Self. Disregard the body and…

5. Building works start

When the disciple Chellaperumal came to Bhagavan, Moksha was all he wanted. But Bhagavan had him start construction work and kept him at it almost exclusively for the next 9 years. It was exhausting physical…